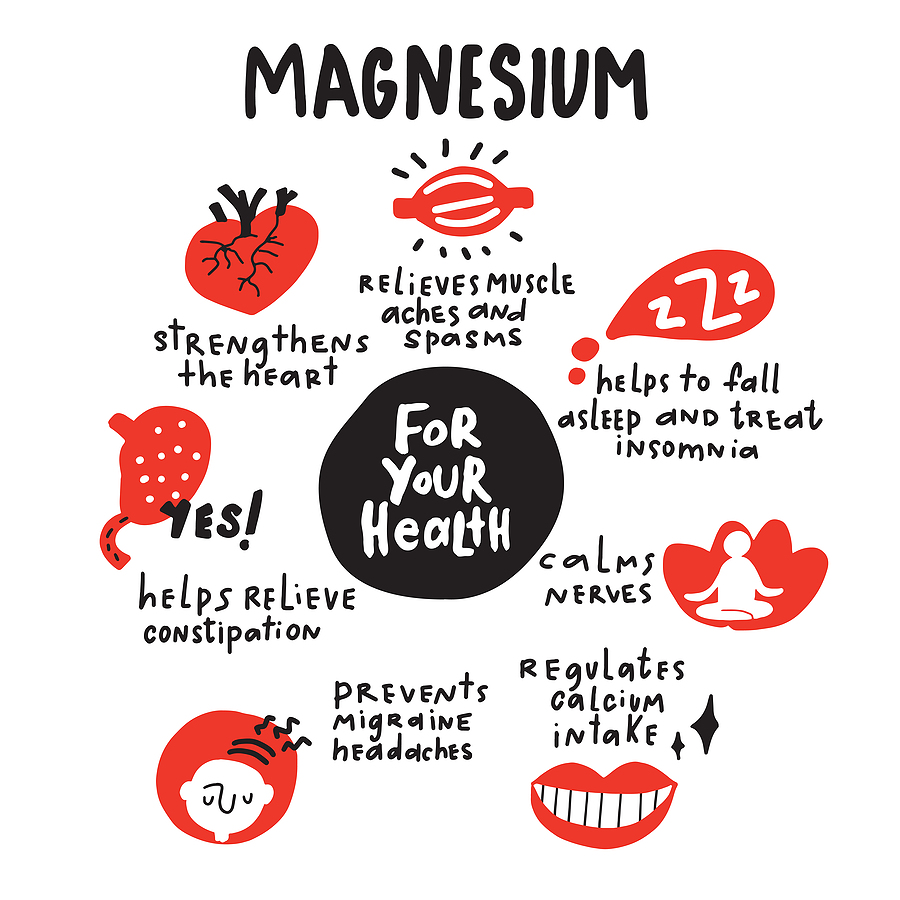

If there’s one supplement that attracts curiosity, it’s possibly magnesium. Perhaps because it seems so multi-purpose. Here are some basics.

It’s true that magnesium does a lot — it’s involved in more than 300 different bodily functions.

While we might think of it as helping with sleep or leg cramps, it also has a role in areas such as blood sugar regulation, energy production, heart health, and bone formation. And that’s just scratching the surface.

Magnesium isn’t produced by the body, so we have to get it from food (ideally) or supplements. Most of it is stored in our bones and other tissues.

The best way to make sure we have a good supply is through what we eat. It’s plentiful in foods such as leafy greens, legumes, nuts, seeds, dairy, whole grains, bananas, avocados, and dark chocolate, but virtually absent from processed foods. So people who rely on those risk becoming deficient.

Other factors that can reduce our magnesium levels include strenuous exercise and/or heavy sweating, alcohol, gut issues such as celiac disease or inflammatory bowel disease, kidney disorders, and some medications (e.g. diuretics and proton pump inhibitors).

If you’ve ever looked for a magnesium supplement, you’ve most likely discovered that there are lots of different types of magnesium. That can be confusing, but what we buy needs to be determined by what we want it for.

The two main types used in supplements, at least in Australia, are probably magnesium glycinate and magnesium citrate, though there’s a string of others — magnesium amino acid chelate, magnesium orotate, and so on. The only one to avoid is magnesium oxide, because it’s not well absorbed.

Magnesium glycinate is commonly used in sleep formulas. Magnesium is thought to calm the nervous system and help us move into a more restful state.

Magnesium glycinate is made from magnesium and an amino acid called glycine, which is found in foods such as meat, fish and dairy. Glycine itself is thought to help with sleep.

A well-known form of magnesium that some people find relaxing — and might help with sleep for that reason — is Epsom salts (or magnesium sulphate) in a bath. It’s also used to soothe sore, achy muscles. So if you prefer to get your pre-sleep magnesium by soaking in it, this might be the way to go.

Magnesium citrate is magnesium bound with citric acid. It’s more likely to be used in products aimed at energy production or muscle and nervous system support. Like magnesium glycinate it’s easily absorbed. Note that it can have a mild laxative effect.

Magnesium is often thought to help with leg cramps, which are both painful and annoying when they disrupt our sleep. Also annoying is that the combination of being female and being older seems to predispose us to more of them.

It’s important to be aware though that cramps aren’t an automatic sign that we’re low in magnesium. They’re linked to a range of sources including medications, dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and exercise.

Medications that might encourage cramps include statins, some antidepressants, and some pain medications, so be sure to read the consumer information that comes with whatever you’re using.

Cramps can also be triggered by vigorous exercise and sweating, which can result in a loss of electrolytes as well as dehydration.

Not that we need physical exertion to become dehydrated. I’ve written before about dehydration becoming more prevalent as we get older. As much as it’s an obvious risk in summer, it can also be an issue in winter if we’re drinking lots of warm, caffeinated drinks. Caffeine is a diuretic, so we could be excreting more fluid (and magnesium) than we realise.

While there are still question marks around the cause of cramps (and why older women have more of them), keep an eye on your hydration and medication, and if you regularly get crampy in particular muscles, try stretching those before bed to make sure you’re not carrying chronic tension there.

Aside from the generic magnesium formulas, another option could be sprays and creams containing magnesium chloride. The action of massaging these into the leg muscles is probably useful too.

If low magnesium is your issue, an Epsom salts bath or a magnesium sleep formula might have the added benefit of reducing the likelihood of cramps.

In relation to some of magnesium’s other roles, we need it for healthy bones because it’s involved in regulating calcium and vitamin D.

But be aware that magnesium supplements can interfere with the absorption of oral bone drugs such as Fosamax (or Alendronate), and you need to separate the two by at least a couple of hours.

Magnesium is also known to relax blood vessels, which is thought to help with blood pressure, migraines and mild anxiety. Unfortunately, its impact on blood pressure only seems to be slight, so it’s not a magic solution.

The best bet here is to focus on food. Potassium is another mineral that’s beneficial for blood vessels, and some foods are high in both magnesium and potassium — leafy greens, legumes, nuts, whole grains, and bananas. In addition, these provide plenty of fibre, which is linked with healthy blood pressure.

The recommended daily intake of magnesium for women over 50 is 320mg.

If you do decide to try an oral supplement, check how much magnesium it actually contains. For example, in say 500mg of magnesium glycinate, there might only be 50mg of magnesium. This will be shown on the label as the amount of ‘elemental magnesium’ or how much magnesium it’s equivalent to.

A lot of magnesium supplements come as a powder because we can ingest more that way. It’s bulky so there’s a limit to how much can be fitted into a tablet or capsule.

Finally, it’s always useful to take account of what else is in a supplement. Some of the more generic magnesium products can come with a long list of ingredients. If you take other supplements that also contain some of those, it’s easy to find yourself unwittingly taking quite a bit of some of the extras.

For example, zinc is a common additive in many supplements (not just magnesium), and if we’re not careful we can be taking more than the recommended dose. High zinc levels can result in low iron levels, and before we know it, we’ve managed to create another issue we don’t need.

Photo Source: Bigstock