The new US dietary guidelines were released this month, to a mixture of applause and disapproval.

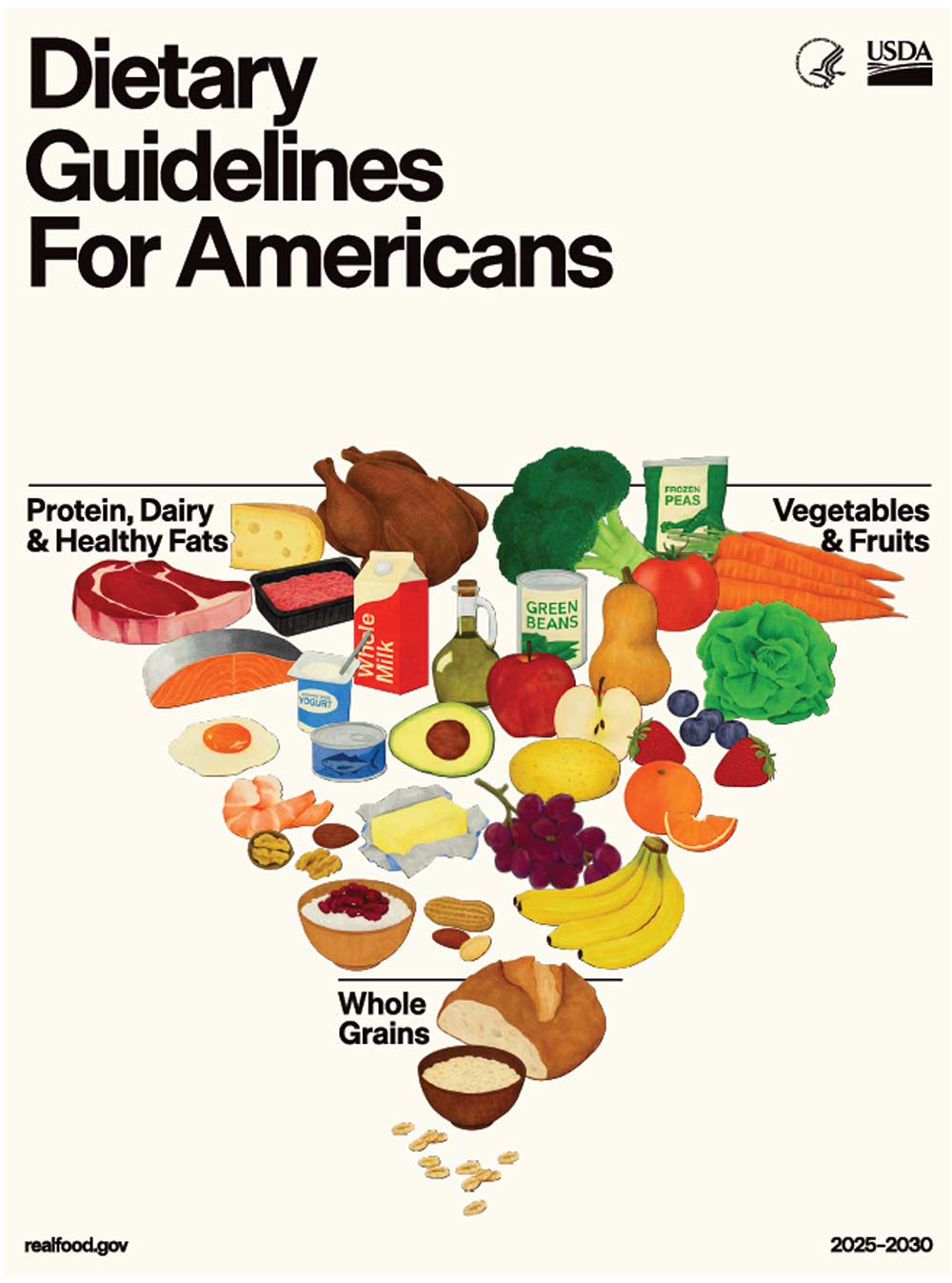

Although the dietary pyramid hasn’t been around for 20 years, it’s still an image a lot of us remember. But now it’s been flipped on its head.

For example, grain-based foods used to comprise the base; now they make up the tip. Fats and oils, which once sat in the tip, are now included in the main part of the pyramid.

In our lifetime, recommendations have danced all over the place, which underlines one thing: there’s no single right diet and we all need to work out what suits us as individuals.

The key message in these new guidelines, though it’s hardly new, is to eat real food.

Aside from the overturned pyramid, the other issue with these guidelines is that they contain a contradiction that makes them impossible to follow — a slight problem. I’ll get to that later.

For now, let’s walk through the eight guidelines. I’ll give you a short-hand version, but you can see the full one here.

I’m going to say from the outset that I think they’re mostly sensible.

- Eat the right amount for you

This emphasises portion size and hydration (drinking water and unsweetened drinks). Straight forward.

- Prioritise protein foods at every meal

The focus is on high-quality, nutrient-dense protein foods. Tick. This guideline encompasses animal proteins (e.g. eggs, red meat, poultry, seafood) as well as plant-based proteins such as legumes, nuts and soy.

The recommended amount of protein is up from .8 grams per kilogram of body weight to 1.2-1.6 grams.

This doesn’t mean we need to get out the scales, but it does mean knowing what does and doesn’t contain protein.

- Consume dairy

Full-fat dairy is encouraged — 3 serves a day. Of course, if you don’t digest some dairy products well you’ll need to adjust for that and find alternatives. (Don’t eat anything, dairy or otherwise, that doesn’t agree with you.)

- Eat vegetables and fruit

No surprises here — a colourful variety, whole, and in their original form, 3 serves of veg, 2 of fruit.

- Incorporate healthy fats

It’s noted that these are plentiful in whole foods, such as meat, poultry, eggs, omega-3-rich seafood, nuts, seeds, full-fat diary, olives and avocados.

Then there are fats we add or cook with, and the three mentioned are olive oil, butter (though ghee is mostly better for cooking), and tallow. If you grew up eating food cooked in tallow or ‘dripping’, this might not thrill you (though tallow’s a lot more pure than dripping). In any case, you don’t need to go there.

Polyunsaturated seed oils don’t get a mention.

But here’s the curly bit.

This section also says: In general, saturated fat consumption should not exceed 10% of total daily calories.

Limiting saturated fat has been part of the guidelines since they were first introduced in 1980. It was thought that saturated fat caused heart disease, in middle-aged men at least.

Although no review using the highest quality data we have (i.e. from clinical trials) has ever found evidence for this, it remains a fixed belief.

Many of the foods given the go-ahead in these guidelines — meat, oily fish, eggs, full-fat dairy, and so on — contain saturated fat, though meat, fish and eggs actually have more unsaturated than saturated fat (dairy is the only food group that has more saturated than unsaturated fat).

Welsh researcher Zoe Harcombe has done a PhD on this. She’s shown that even lean meat and low-fat milk contain more than 10% of saturated fat. Avocados have 20% saturated fat, and olive oil is around 10-15%.

In fact, all foods that contain fat contain all three fats — saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated. And the only food that doesn’t contain a trace of fat is sugar.

As Dr Harcombe points out though, nature didn’t put saturated fat in everything from fish to fruit and beef to broccoli to kill us.

(As it happens, Krispy Kreme doughnuts just slip through on 9.9%. Luckily, nature had nothing to do with those.)

So it’s nigh on impossible to follow the guidelines and limit saturated fat to 10% of daily calories. We can do one or the other, but not both.

Why were they released with such a glaring contradiction? Probably politics and trying to appease certain groups or individuals, but it’s tricky given the provision of food in facilities such as schools, hospitals, and prisons is supposed to comply with dietary guidelines. Presumably most will just do what they’ve always done.

The document also says that significantly limiting highly processed foods will help meet this goal (true, but not enough to make it achievable), and that more high-quality research is needed to determine which types of dietary fats best support long-term health (not true, we already have oceans of evidence on this; we just need to acknowledge it).

- Focus on whole grains

Prioritise fibre-rich whole grains, significantly reduce the processed ones (e.g. white bread, cereals, tortillas, crackers), and adjust consumption of grains according to our caloric needs. Again, straight forward.

- Limit highly processed food, added sugars, & refined carbohydrates

Self-explanatory. Mentions limiting food and drink containing artificial flavours and preservatives, petroleum-based dyes, and low-calorie non-nutritive sweeteners, plus avoiding soft drink, fruit drinks, and energy drinks.

- Limit alcoholic beverages

Drink less alcohol for better overall health. Especially if you’re pregnant, have a problem with managing alcohol, or take medication or have a condition that doesn’t go well with alcohol.

The Three Boxes

In addition, there are three boxes – on Gut Health, Added Sugars, and Sodium (salt).

The Gut Health one acknowledges that highly processed foods can disrupt the balance of our microbiome, and that vegetables, fruits, fermented foods and fibre support a diverse microbiome which may be beneficial for health.

The box on Added Sugars helps us identify sugar on a food label since it can be given a multitude of other names.

And the one on Sodium notes that highly processed foods are high in sodium and should be avoided.

Special Populations

Finally, there’s a section on the needs of various groups, including infants and toddlers, adolescents, pregnant women, older adults, people with chronic disease, and vegetarians and vegans.

For older adults it’s noted that although we might need fewer calories, we still need key nutrients such as protein, B12, vitamin D and calcium. The best source of these is a nutrient-dense diet. When dietary intake or absorption is insufficient, we might need fortified foods or supplements.

It’s noted that people with certain chronic diseases might benefit from a lower carbohydrate diet. Given that most Americans are overweight or obese and almost one-third of adolescents in that country have pre-diabetes, that recommendation could apply to most of the population.

The piece on vegetarian and vegan diets says they can fall short on a range of vitamins and minerals.

Since the release of the guidelines there’s been quite a bit of pearl clutching in some quarters about the endorsement of red meat, eggs, full-fat dairy, and so on. That was always going to happen.

But harking back to Zoe Harcombe, lamb roasts, scrambled eggs, and full-fat yoghurt are not going to be the source of our demise.

It’ll be interesting to see how America responds, and whether the next Australian guidelines are swayed by any of this. Probably not, but time will tell.

Image Source: https://cdn.realfood.gov/DGA.pdf